To engage with the spectrum of American music is to embrace an idiosyncratic, sometimes archaic worldview of inclusivity, pluralism, and diversity. After all, a genre like jazz owes as much to African polyrhythmic structures as it does to ragtime, blues, and European military band music. Appalachian music draws as freely from its origins in Irish and Celtic traditional music as it does with African-American blues, English ballads, and Anglican hymns. To be fully American is first to recognize this multilingual heritage of cultural and stylistic antecedents, and subsequently to channel these myriad sources into a unique language of one’s own.

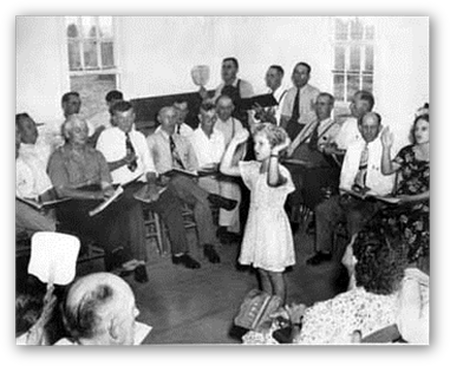

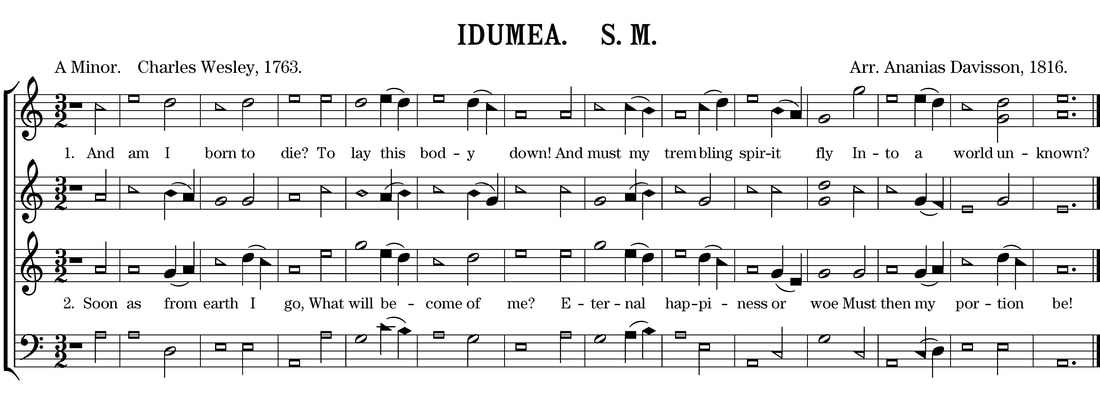

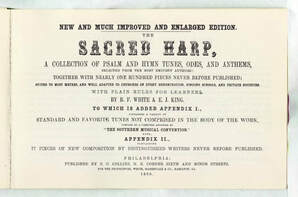

In particular, one of these singular strains of American music with a particular New England – and, for that matter, South Shore – connection is the Sacred Harp music of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Sacred Harp singing is a tradition of sacred choral music originating in New England between 1770 and 1820, with roots stemming back to the four-part counterpoint of the Anglican Church. The term “Sacred Harp” is synonymous with the human voice, and takes its name from a historically significant book published in 1844. All Sacred Harp music is shape-note music, a didactic genre where syllables of a specific solfege alphabet were sung as a way to teach musically illiterate persons how to sing. As participatory artistic practice with no requirement even of musical literacy, Sacred Harp was a potent democratizing force in congregational New England. Massachusetts was an important center of Sacred Harp composition and publication, thanks in large part to composers such as the Bostonian tanner William Billings, Supply Belcher of Framingham, and Jacob French of Stoughton.

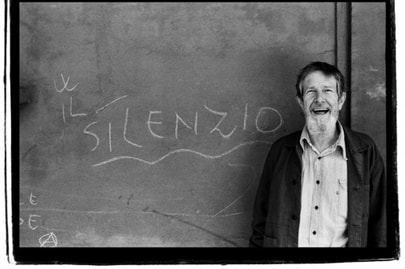

Let’s jump back into our time machine and fast-forward two hundred years, to Boston in September of America’s bicentennial year, 1976. On September 29th, John Cage’s sprawling commission Apartment House 1776 was premiered in Boston, which included his 44 Harmonies, which were Cage’s re-imaginings of Sacred Harp hymns arranged for string quartet. In his 44 Harmonies, Cage resets these old hymns in new ways by omitting or adding voices, interspersing silence, and applying 20th-century, anachronistic sonorities to this 18th-century repertoire. Cage works within the original tunes, plays with them, distorts them, and what remains is a contemporaneously relevant conversation between the old and the new

On February 24th, I curated a program at South Shore Conservatory in Duxbury, MA, comprising these two bodies of work set in clear dialogue with one another. Along with my quartet-mates Emily Hale, Daphne Manavopoulos, and Lauren Nelson, we presented a judicious selection of these four-part songs for string quartet were divided into four “hypersuites,” titled: South Shore, Redemption, Midwinter, and Rapture. In South Shore, Sacred Harp tunes and Cage harmonies with familiar titles such as Hingham, Weymouth, Duxbury, Scituate, Cohasset, and Bridgewater. In Redemption, Sacred Harp and Cage are set against the raucous and idiosyncratic string quartet written by Benjamin Franklin (yes, that Benjamin Franklin!), written for string quartet without the use of the left hand. In Midwinter, we explored themes of darkness, seasonal change, and death. To close, Rapture celebrates the transcendent, the euphoric, and the ecstatic in music, book-ended by Supply Belcher’s gorgeous hymns titled “Rapture.” In the link above you can hear an abridged version of the longer live 4-part concert program.

Our string quartet chose to perform this program on historical instruments in a historically-informed 18th-century style, including the John Cage selections from 1976. During the American colonial era, string instruments would have been strung with gut strings (as opposed to steel strings today), which, along with lighter bows, thicker bridges, et al., gives these instruments a rough, earthy sound that is truly “of the flesh.” Additionally, this was performed at South Shore Conservatory's campus in Duxbury, which is a converted New England church and as such a lively and resonant acoustical space. To perform early music on early instruments in a resonant space, is to hear this music afresh, perhaps as it was truly meant to be heard.